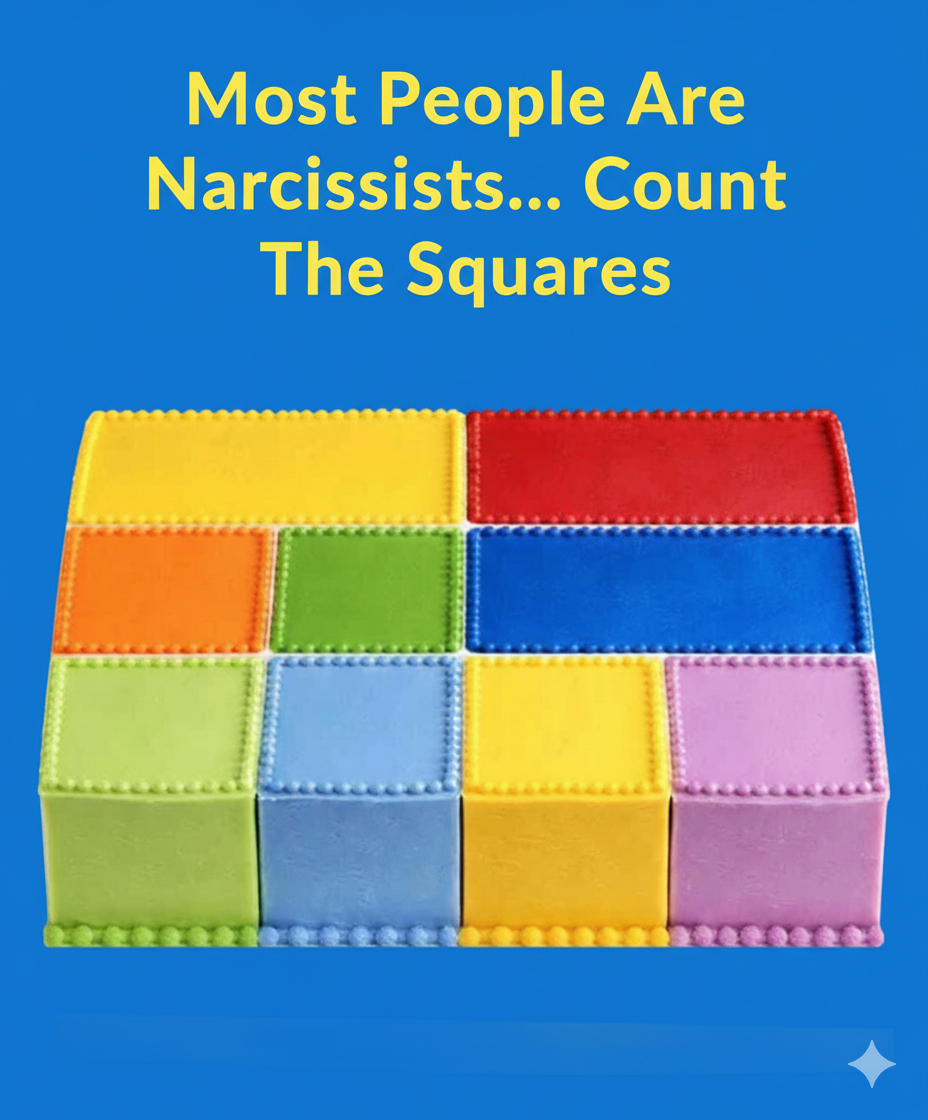

At first glance, a “count the squares” puzzle seems simple: a stack of geometric blocks challenges viewers to tally the visible shapes. Many scroll past, assuming a quick glance will suffice. Yet when you pause to actually count, the task becomes surprisingly tricky. Some squares are obvious, while others are partially hidden or overlap, forcing observers to reconsider their initial impressions and approach the puzzle carefully.

These puzzles rely on visual perception rather than arithmetic. Top-facing squares are easily counted, but front-facing or partially visible squares require extra attention. Some players even imagine hidden layers to calculate a full 3D total. Different approaches yield different answers, none strictly “wrong.” The divergence reflects how humans perceive, filter, and prioritize visual information, shaped by expectations, attention, and cognitive biases.

Beyond perception, the puzzle shows how ego influences responses. Provocative captions claiming “most people are narcissists” prompt defensiveness over curiosity. Comment threads often escalate into debates, demonstrating how pride can interfere with problem-solving. These reactions highlight confirmation bias, selective attention, and anchoring—cognitive tendencies that affect both puzzles and real-life decision-making.

Ultimately, the lesson goes beyond counting squares. Perspective, patience, and clear definitions matter in all challenges. By considering multiple angles, setting rules upfront, and remaining open to alternative interpretations, individuals improve reasoning, attention, and collaboration. The puzzle’s true purpose is not the number of squares but how we approach complexity, handle uncertainty, and learn to see clearly.